- Home

- Michelle Morgan

The Girl Page 8

The Girl Read online

Page 8

Some of them have kidded you into believing you could become a great dramatic actress. Only the other day you said yourself that you’d like to appear in a film based on Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov. Have you ever read the book? Why not choose some pleasant trifle like the balcony scene in Romeo and Juliet? That would be fun…

One must ask if columnists such as Coulter ever chastised the male species for wanting to better their lives. It is doubtful. The fact remains that for a woman with ambition in the 1950s, life was filled with sexism and disbelief. During Marilyn’s last interview, in 1962 with Richard Meryman, one of her requests was that the reporter not make her look like a joke. After being mocked during her entire career, it is easy to see why such a wish was made.

The idea of any actress—not just Marilyn—owning a production company, caused a furor in the male-dominated industry. However, a look at some statistics shows exactly why it came as a surprise. Firstly, the only mega-famous female movie mogul had been Mary Pickford, and her producing days were over by the 1950s. (Her last film was Love Happy [1949], which included Marilyn in a walk-on role.) A search of the phrase “female producer” in the hundreds of film magazines scanned on the Media History Digital Library brings up only nine results. None of those articles were written later than 1947. The same search in the Los Angeles Times and New York Times shows just one entry during the entire 1950s: a report entitled “Story of a Determined Lady,” about theater producer Terese Hayden. Within the columns of the story, the ambitious woman is described as a “girl producer.”

The phrase “woman film producer” fares hardly any better. Twelve articles appear in film magazines, with only two of those being after 1943. The same search in newspapers brings up only two results for the 1950s. While Marilyn is proof that some women were striving to be successful in the production side of filmmaking, as far as the industry was concerned, the concept was rarely spoken about and certainly not nurtured or encouraged. It was fine to look pretty in front of the camera, but to be powerful and successful behind it was a joke of magnificent proportions.

One reporter asked if Marilyn would like to be a director too and she shook her head, saying that she simply did not have enough experience. She was being a tad unfair to herself, because history has shown that she was actually something of a genius when it came to still and moving cameras. She knew instinctively how to pose to create the perfect photograph, and saw even publicity shoots as important work. Photographer Richard Avedon later said that Marilyn was always completely involved with her photo shoots and shared many ideas and thoughts, even working throughout the night if she thought the occasion required it.

Reporter Sidney Skolsky once watched as she posed for the March 1954 cover of Modern Screen magazine. He wrote that she began work at 12:30 p.m. and did not finish until 4 p.m. “I act when I’m posing,” she explained. “Just as hard as I do when I’m playing a role in front of a movie camera. I think of something for each pose so I’ll have the right expression.”

A list made in her notebook shows that she made plans to attend directorial lectures by Harold Clurman and Lee Strasberg, so she might have quietly hoped to one day become a director—although after the furor caused by the revelation of her producing ambitions, she was highly unlikely to admit it to the press. Years later, during the making of The Misfits, Marilyn jotted down ideas on how certain scenes should be shot; she was clearly intrigued by the process.

Should she have gone down that road eventually, Marilyn would likely have been taken even less seriously than she was already. All searches for “female director” and “woman film director” in film magazines and newspapers come up with only a handful of results, and all were printed before 1943. Trailblazer Dorothy Arzner was the exception in the otherwise male-dominated industry. She started as a typist at the Famous Players-Lasky Corporation (later Paramount), but through hard work and determination had managed to become a director. By 1932, she was working independently, and in 1936 was said to be the only female director in Hollywood. In 1937, Arzner told the Los Angeles Times that as a lone female director, she must never raise her voice on set or act in what some might consider an unreasonable way. According to her, society still expected her to be feminine, and swearing was totally out of the question. By 1938, the Motion Picture Herald told readers that not one female director was under contract to any of the top fifteen producers, and by 1943, Arzner had directed her last movie.

In Great Britain, the situation was no better. The British Newspaper Archive shows no results for “female film producer” and only two listings for “female film director.” Both articles are from the 1940s. Those women who dared to try their luck in the industry were met with sarcasm or disdain by the British press. An article in the Dundee Evening Telegraph in 1940 bore the headline “They’re Doing a Man’s Job” and announced that Mrs. Culley Forde was the only woman associate producer in the entire British movie industry. She could not enjoy her success alone, of course. Instead, the newspaper made sure to mention that she was the wife of director Walter Forde.

A piece in the Sketch from 1946 is even worse. Entitled “We Take Our Hat to Miss Jill Craigie,” the newspaper celebrated Craigie’s status as the only female film director in England. However, they chose to do so not with a list of her most important work, but with two pages of photographs showing her admiring her face in the mirror, laying the table for dinner, walking up the stairs, doing her hair, and reading. Of course, they also mentioned that she happened to be the wife of film director Jeffrey Dell. “Jill Craigie rightly pays as much attention to her personal appearance as she does to production details,” it said.

CHAPTER FOUR

A Serious Actress

WHILE SETTING UP HER film company was momentously important for Marilyn, she also knew that if she was going to do great work, she needed a solid foundation from which to start. This meant exploring acting techniques that were new and fresh, and walking away from existing coach Natasha Lytess. In the past, the firing of Lytess has often been regarded as a cold, uncaring decision on Marilyn’s part. However, before judging her action, it is important to understand the nature of the relationship and the kind of person Lytess was.

Marilyn first met the woman in 1948, during her six-month tenure under contract to Columbia Pictures. Lytess was a teacher there and was asked to help the young actress with her voice and dramatic training. She recognized straightaway how nervous Marilyn was, but instead of giving her confidence and putting her at ease, Lytess recoiled at the sound of her voice. “She was in a shell,” she said. “She couldn’t speak up. She was very inhibited. I had to ask her not to talk at all. Her voice got on my nerves. She’d say, ‘all right, thank you, g’bye.’ I taught her to let go.” It is worth noting that this insulting comment was not given to the press after their association ended, but in 1952, when they were still working together. Natasha Lytess never had any qualms about telling people about her famous client, and to say she thought herself totally responsible for her career would be an understatement.

Marilyn wasn’t the first or the last student who had problems with Lytess. In 1951, actor Fess Parker had an unfortunate run-in with her that was not dissimilar to the one Marilyn had a few years before. He told the Los Angeles Times that Lytess had asserted that he was “practically un-coachable,” and while she mellowed slightly by telling the young actor that he had a certain quality, she never did explain what she meant by the enigmatic remark.

Lytess later claimed to be totally unimpressed with the young Monroe, and declared her to be not at all beautiful. In fact, she made it plainly obvious that she considered Marilyn to be beneath her in both status and talent. “Her face was as wooden as a ventriloquist’s dummy…. She was tense and apprehensive, utterly unsure of herself. Unable even to take refuge in her own insignificance.” Lytess was jealous that she had never achieved great success as an actress herself, and was somewhat obsessed with the young starlet in her care. Lytess maintained that while Mar

ilyn insisted she be on film sets with her at all times, the coach actually felt uncomfortable to be there. This would be far more convincing if not for the fact that Lytess took over the entire set of every production she worked on, as attested by many a director over the years.

Sitting next to the director, the coach could be seen copying everything Marilyn did before the camera. Then the moment the director cried “Cut,” she would often clench her fists, shout her disapproval of what had just occurred, and then rush to Marilyn’s side to tell her what she had done wrong. She would also act as something of an unofficial (and unappointed) manager, who enjoyed telling reporters that they could go through her for an interview with Marilyn.

At one point the two women shared a house (along with Lytess’s daughter and a maid) so that they could practice all day, every day. While in theory this was good for preparation, it also meant that Marilyn had little freedom and even less privacy. Lytess would often grow jealous and resentful of relationships Marilyn had with men, but the actress tolerated this aspect of her personality because she wanted help with her acting studies. The arrival of Joe DiMaggio in 1952, however, caused the first cracks to form in their relationship, since Lytess hated his presence in Marilyn’s life and he was in no hurry to leave.

Another problem was the coach’s obsession with publicity. Over the years of working with Marilyn, she would speak about her openly to any reporter who asked. Just days before the beginning of The Seven Year Itch, she even appeared on the television show What’s My Line as Marilyn’s coach. One must wonder if she had obtained her student’s permission before signing up to do the program. By the end of 1954, when Marilyn was getting ready for her move to the East Coast, she finally took the decision to leave Lytess behind in Los Angeles. Perhaps predicting a dramatic reaction, she did not tell the coach that she was actually fired; instead, she kept quiet and hoped Lytess would figure it out for herself. She did not.

By March 1955, the drama teacher was still in the dark and columnist Hedda Hopper was eager to talk to her about it. Asked if she had been contacted by her errant student, Lytess said she had heard “not a peep.” She was worried, she said, because the time was right to follow up The Seven Year Itch with “more fine pictures.” Perhaps in a misguided attempt to create a reaction from Marilyn, Lytess was quick to tell Hopper that she was now teaching two other actors: Jeff Hunter and Virginia Leith.

Eventually Natasha Lytess woke up and realized that Marilyn was not going to come back. In retaliation, it did not take her long to contact reporters about their relationship. In an article entitled “The Storm About Monroe,” writer Steve Cronin interviewed various people on the subject of how Marilyn had changed from Hollywood glamour girl to dramatic actress. One of the people he spoke to was an unnamed woman, described as “one of the few women in Hollywood who has worked with Marilyn closely for many years.” Since Natasha was the only one who fit the description, it can be assumed that the quote came directly from her. “I have come to the conclusion,” she said,

that Marilyn Monroe doesn’t know her own mind. I can’t tell you how unhappy she was while she was married to DiMaggio. She felt closed in, a prisoner in her own house. She felt that Joe never would come to understand either her or show business. Her months of marriage to DiMaggio, despite all the fairy tales, were months of misery.

When she divorced Joe, I know she felt as though a great weight had been lifted from her heart. She and Joe had nothing in common. She told me this a dozen times if she told me once. Marilyn has had very few friends in her life. Because of her sex appeal, women are afraid of her. The men she has known usually have been instrumental in helping her career. Joe was not one of these and she let him go…. What does all this mean? Does anyone really know where Marilyn is going? What does she want? What sort of woman has she become?

It is unrecorded as to what Marilyn’s feelings were toward Natasha’s outbursts, but certainly during the early months of 1955, her mind was on other matters. After she’d lived for a while with the Greenes, it was felt by all parties that Marilyn needed a base in the city as well. So it was that on January 19 she moved into New York City’s Gladstone Hotel, a private space paid for by business partner Milton Greene, as per his contractual agreement. Despite the end of her marriage to Joe DiMaggio, he was seen helping Marilyn move into the hotel and then eating with her at various locations around town. Rumors swirled that the two were about to be reunited, especially when she met him in Boston while on a business trip to see a possible Marilyn Monroe Productions investor. The investment did not go ahead, but the visit nevertheless managed to garner headlines.

As the couple left a restaurant in the company of his brother and sister-in-law, journalists pounced and asked if this was a reconciliation. Joe looked at his ex-wife and asked if it was, to which Marilyn replied, “Well just call it a visit.” This was obviously not the answer the baseball player was looking for, because as soon as they got away from the reporters, he dropped her off at her hotel and headed to the home of his sister-in-law’s parents. The next day journalists managed to track Joe down and interviewed him on the doorstep, Joe still wearing his bathrobe. When asked again about the reconciliation, he shrugged. “There is none,” he replied.

In the end, any hope of the couple getting back together was a figment of the media’s imagination. Joe might have seemed rather keen on the idea, but Marilyn was adamant that she was now single and would stay that way. As happy as she was to be on friendly terms with her ex-husband, the brutal divorce and events leading up to it were still fresh wounds. For now, there would be a friendship between the pair, but it was strictly on Marilyn’s terms; she was firmly in control.

On January 25, she was happy to accompany Joe to see him elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame. This meant a lot to the former baseball star, and for once he was talkative to the reporters who wanted to know about it. “You can bet I’ll be there with flying colors,” he said. “I’m very excited about this. And I’m especially happy because it will mean so much to my son, Joe Junior.”

January 26 arrived and Marilyn gave an interview to author George Carpozi Jr. and took part in an accompanying photo shoot in her suite at the Gladstone. The chat was candid and the two ended up walking arm in arm through Central Park as Marilyn told the story of her life. Carpozi would treasure the memories of meeting the actress, and later compiled everything he remembered into a book, one of the earliest ever written about Marilyn and one she had in her own collection.

Through author Truman Capote, Marilyn was introduced to teacher Constance Collier, a British Edwardian actress who had moved to Hollywood in the 1920s. There, she taught students how to transition from silent movies to talkies and acted in a few herself. By 1955 she was settled in New York, and it was there that Marilyn became her student. At first Collier had little interest in meeting the actress because the only knowledge she had of her was through the grand buildup of publicity Marilyn had received since the beginning of her career.

She did not know how she would take to the blonde icon, but after speaking to her for the first time, Collier soon realized that Marilyn was actually a fragile talent. “My special problem” was how she described the actress to Capote. Together they studied the character of Ophelia from Shakespeare’s Hamlet, and when Collier spoke to Greta Garbo about it, the great Swedish actress suggested maybe she and Marilyn could work together one day. This must surely have thrilled Marilyn, since she was a great fan of Garbo as a woman and an actress.

Sadly, the relationship with Collier did not survive past a few months, since the woman’s health deteriorated and she passed away in April 1955. Marilyn never forgot the great work they achieved in class, however, and attended her funeral with Capote.

CREATED IN 1947 BY Elia Kazan, Cheryl Crawford, and several others, the Actors Studio was one of the most prestigious acting institutions in the United States. A common misconception was that it was a formal acting school, but actually the studio was run in the style of a

workshop and attended by actors who were required to audition in order to gain full membership. Once in the door, students could congregate, work on scenes, receive emotional guidance, correct errors, and solve problems. Most of the actors had already received some kind of training elsewhere and were now looking for a kinship, a safe place to learn emotional—rather than technical—training.

In 1951, teacher Lee Strasberg took charge of the studio, and his wife, Paula, was frequently by his side. A staunch supporter of Konstantin Stanislavski, Lee and several other teachers had taken inspiration from the System technique and evolved it into the Method, which was what the Actors Studio became infamous for. The aim was to enable actors to relax into their parts, by digging deep into their own emotions and memories. This would allow them to bring up personal episodes that would give a better understanding of the acting role.

The process was a deeply personal and even spiritual experience, and as such, it became highly controversial to those actors who preferred a more technical approach. Method director Charles Marowitz wrote about the problem in 1958, explaining that it was all just a question of balance. “No Method-man from Stanislavski onwards has ever contended that [the Method] dismisses the need for vocal and kinesthetic competence.” In fact, he assured readers, Stanislavski himself said that the Method (or the System, as it was called in his day) was really there to inspire actors to develop styles and processes of their own.

Lee Strasberg actually understood that the Method wasn’t a good choice for everyone, and that every actor required different tools to solve their problems. However, he was determined that the work done at the studio would be of great assistance to those who needed it. He also desperately wanted to provide the kind of support that the general American theater did not—the kind of emotional stability and variety that repertory theatre gave actors in Great Britain.

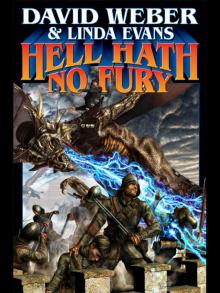

Hell Hath No Fury

Hell Hath No Fury The Mammoth Book of Hollywood Scandals

The Mammoth Book of Hollywood Scandals Marilyn Monroe

Marilyn Monroe The Girl

The Girl Racing the Moon

Racing the Moon