- Home

- Michelle Morgan

The Girl

The Girl Read online

Copyright

Copyright © 2018 by Michelle Morgan

Cover photo photographed by Milton H. Greene © 2017 Joshua Greene

www.archiveimages.com

Back cover photo courtesy Everett Collection

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

Running Press

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.runningpress.com

@Running_Press

First Edition: May 2018

Published by Running Press, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Running Press name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Marilyn Monroe cover photograph by Milton H. Greene is registered with the Library of Congress and protected by United States copyright laws. The photo is not included in the copyright of this published work. All rights are reserved by Joshua Greene. Separate written permission is required for reproduction by any other publisher. Contact The Archives, LLC, 2610 Kingwood Street Suite #3, Florence, Oregon 97439 T# 541-997-5331. www.archiveimages.com [email protected]

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017961025

ISBNs: 978-0-7624-9059-2 (hardcover), 978-0-7624-9060-8 (ebook)

E3-20180417-JV-PC

Contents

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

DEDICATION

INTRODUCTION

PREFACE: Rebellious Starlet

CHAPTER ONE: The Girl

CHAPTER TWO: No Dumb Blonde

CHAPTER THREE: Behind the Tinsel

CHAPTER FOUR: A Serious Actress

CHAPTER FIVE: The Unlikely Feminist

CHAPTER SIX: Inspirational Woman

CHAPTER SEVEN: Performance of a Lifetime

CHAPTER EIGHT: The Woman Who Impacted the World

CHAPTER NINE: The Power Struggle

CHAPTER TEN: The Human Being

EPILOGUE: Passing the Torch

PHOTOS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

APPENDIX: A Woman of Culture

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

SOURCE NOTES

This book is dedicated to:

Jim and Zena Parson. I will never forget your kindness. Thank you so much for all you’ve done for me.

And

My beautiful and immensely talented friend, Gabriella Apicella. I’m sure Marilyn would have loved you, just as much as I do.

Introduction

WHEN I FIRST DISCOVERED Marilyn Monroe, it was 1985 and I was a teenager. I was at first attracted to her beautiful, glamorous image, but the moment I began reading about her, my feelings went far deeper. I soon realized that Marilyn had become a highly successful woman despite having many odds stacked against her. While her ultimate story was one of tragedy, the woman herself was a fighter, someone who began life as Norma Jeane—a little girl who lived in a series of foster homes—and yet fought her way to become not only an actress, but one of the most famous women in the entire world.

Yet while I could quite clearly see that Marilyn was an intelligent person, I found myself forever bombarded with comments such as “Oh, she was just a dumb blonde” or “You can tell she’s just playing herself on-screen.” These statements baffled me and always came from people who knew nothing at all about her (nor wanted to learn). More than thirty years later, I have covered aspects of Marilyn Monroe’s life in five books and find myself still dispelling myths, correcting untruths, and trying to educate people on one of the most universally intriguing stars of the cinematic pantheon. Happily, now many want to learn what Marilyn was really like. But it cannot be denied that history has been rewritten in the decades since her death, and the woman who achieved so much in the 1950s is often lost in a haze of modern-day Internet memes and rumors. I regard this book, therefore, as a means of redeeming her reputation.

The Girl, titled after her character in the 1955 comedy The Seven Year Itch, tells the story of how that film transformed Marilyn Monroe from another Hollywood star into “The Girl” of modern times—a true icon—and sent her on an unparalleled adventure of self-discovery and reflection. The years 1954 to 1956 were Marilyn’s most powerful and inspirational, and it was during this time that her most substantial decisions were made. Before Itch, she had been known for her mostly fluffy, dumb-blonde roles, and she was unhappily married to baseball legend Joe DiMaggio. But by the time the film opened, Marilyn was the president of her own film company, a student at New York’s Actors Studio, and embroiled in a battle with Twentieth Century Fox that would eventually gain independence not only for herself, but others working under the constraints of the studio system too. Shortly after the release, she legally changed her name to Marilyn Monroe, thereby divorcing herself from the troubled past of Norma Jeane once and for all. Her rebellion was remarkable and exceptionally rare during a time when women were expected to strive to be fantastic homemakers and actresses had to accept every kind of behavior imposed upon them by their male bosses.

While The Seven Year Itch played a pivotal part in Marilyn’s life, so it did in mine too. I can remember the exact date when I first watched the movie: it was December 24, 1986, and I was sixteen years old. I had been a fan for just over a year and had seen only a few of Marilyn’s movies at that point. I desperately wanted to see The Seven Year Itch because of the famous skirt-blowing scene, but what I remember most of all is just how luminous Marilyn Monroe looked in the film. Her hair, her skin, her costumes—everything glowed, and the magic of her personality shone straight out of the screen.

At some point during the evening, my grandparents came to visit. They sat down and watched the film with me, laughing when Marilyn made quips about keeping her undies in the icebox, and making comments about her strange habit of dunking potato chips in champagne. My grandparents were born just three years before Marilyn, which made her a star of their generation, not mine. However, I don’t ever remember them querying why their granddaughter was suddenly so obsessed with her. It was merely accepted that Marilyn—and The Seven Year Itch—could transcend generations and entertain in the same way they had during the 1950s.

Thirty years later, my thirteen-year-old daughter sat down to watch the same film and declared Marilyn to be “so pure.” This made me smile. The magic of The Girl, The Seven Year Itch, and, of course, the actress captured the imagination of a teenager once again. And so it is that Marilyn’s influence continues to inspire each new generation.

Marilyn always searched for ways to make her life more meaningful and profound. She was an exceptionally modern woman and fought the studio and her male bosses as if it were the most natural process in the world. She was glamorous but not scared to be seen without makeup. She could be flirtatious but demanded respect. She posed nude and totally owned the fact that she had done so. In an era of female restraint, Marilyn was an unlikely feminist and a person of such determination that she never ceased to amaze anyone lucky enough to meet her. In turn, her life, work, and rebellion have impacted the lives of people around

the world.

This book presents Marilyn Monroe in a fresh light: strong, independent, brave, and authentically unique; a woman of Yeats, Shakespeare, Chekhov, and Tolstoy; a real-life human being who strived to better herself through education and action. Marilyn Monroe continues to inspire women well over half a century since her death. The Girl explores the many different ways this has come to pass.

—Michelle Morgan, October 2017

PREFACE

Rebellious Starlet

NORMA JEANE BAKER ALWAYS had a rebellious streak. As a child in the 1930s, she had sneaked out of her strict foster parents’ home to see a movie. Being told she’d go to hell for it did little to curb her desire to go again. Then, while living in an orphanage, she and a group of friends were dared to scale the hedge and run away. Norma Jeane was only too happy to get involved, but was soon caught and severely reprimanded for her trouble.

In 1942, the sixteen-year-old was actively encouraged to marry the boy next door, James Dougherty, which would allow her foster parents to make a guilt-free move out of state. She went through with the marriage, though never became a contented housewife. When her husband was sent abroad during the war, the teenager moved in with the Doughertys and started work in a local factory. However, this soon turned into a period of rebellion after she was spotted by a photographer who recommended she start a modeling career. Norma Jeane grabbed the opportunity with both hands and signed with the Blue Book Modeling Agency in Hollywood. There, she was coached by agency boss Emmeline Snively and told that she would go far if she dyed and straightened her brunette hair. When her in-laws started complaining about her interest in this newfound career, Norma Jeane moved out of their house, and in 1946, she traveled to Las Vegas to obtain a divorce from her husband. Shortly afterward, the model landed a contract with one of the top movie studios, Twentieth Century Fox, and assumed the identity of Marilyn Monroe.

After a few false starts, Marilyn’s star began to rise, but for the most part, she found herself playing the role of dumb blonde in film after film at Fox. For a while she was content to work this way because she was simply happy to have a job. When asked if she felt so-called cheesecake/glamour roles would interfere with any dramatic plans she might have, Marilyn was steadfast in her opinion. “Oh, I don’t think so,” she said. “I think cheesecake helps call attention to you. Then you can follow through and prove yourself.”

In March 1952, Marilyn’s burgeoning career threatened to implode when it was discovered that she had posed for nude photographs during her modeling days. Three years earlier, the unemployed starlet had been living at the Hollywood Studio Club and was behind on her rent and car payments. Faced with being homeless and remembering that a photographer by the name of Tom Kelley had once asked her to pose nude, she phoned him in the hope that he could help. A short while later she reclined on a red velvet sheet while Kelley took a handful of photographs of her au naturel. Today the snaps are considered artistic, but in the late 1940s they were scandalous, so to protect herself, the actress signed the model release form as Mona Monroe. Since Marilyn had already posed seminude for artist Earl Moran earlier and never been recognized, she convinced herself that the Kelley pictures would never be seen, picked up her $50 check, and paid her bills.

Eventually Tom Kelley sold the photographs to a calendar company and they caused a sensation. Because of the calendar’s popularity, it did not take long for word to reach the offices of Twentieth Century Fox. Vice president of production Darryl F. Zanuck was outraged and instructed the actress to categorically deny that she was the model in the photographs. Once again, however, Marilyn’s defiant nature shone through. She absolutely refused to say the girl was not her, and instead admitted the story was true and released a statement with her version of events: “I was broke and needed the money. Oh, the calendar’s hanging in garages all over town. Why deny it? You can get one any place. Besides I’m not ashamed of it. I’ve done nothing wrong.”

While Twentieth Century Fox thought the starlet had completely sabotaged her own career, Marilyn contacted several columnists to tell them how worried and nervous she was to hear the reaction of press and public. This was a genius move on her part, because it encouraged the reporters to write sympathetic articles about her predicament. “If anything, the busty, blond bombshell probably has just struck a gold mine,” wrote Gerry Fitz-Gerald. “She is the favorite movie actress of practically every garage mechanic and barber in Hollywood.”

Fitz-Gerald was correct. The honesty with which Marilyn owned the drama, coupled with the story of her penniless situation, touched the hearts of the public. Instead of vilifying her, fans sympathized with her plight and admired the fact that she had finally been able to achieve success. When it was discovered that she was dating baseball legend Joe DiMaggio, it became the ultimate Cinderella story: the girl who once had no pennies to rub together had now met her Prince Charming. Newspaper columnists and the public were ecstatic, and Marilyn had won her first battle as a star.

At the same time Marilyn was admitting to the nude calendar, German actress Hildegarde Neff was causing outrage after performing a nude scene in the film The Sinner. When she arrived in New York City to promote the US release, columnist Earl Wilson asked if she condemned Marilyn for posing for the nude calendar. “No!” Neff snapped. “I’m for her. She won. The public accepted her. She needed a job. Nobody’s attacked her for it.” Wilson asked if the actress thought it paid to go nude. “No, it doesn’t pay to go nude,” Neff replied. “It pays to be honest.”

Marilyn survived the scandal with dignity intact, but someone not so lucky was Phil Max, a fifty-year-old camera shop owner in Hollywood. He had watched the story carefully and in 1953 bought a supply of the calendar for his store on Wilshire Boulevard. Displaying one of the items in the window, Max enjoyed brisk sales for the next two weeks. Unfortunately for him, this success ended when passersby noticed a group of junior high school students giggling and pointing outside the shop. The police were called and Max found himself arrested for violating an ordinance forbidding the display of nude photos that could be seen from the street. Several days later, the man appeared in court, where he pleaded guilty and was fined $50. Just like Marilyn, he was not apologetic. “I didn’t think there was anything wrong with putting the calendar in the window,” he said. “And I still don’t. I’ve seen pictures like that displayed in lots of places.” Someone else who didn’t see anything wrong was entrepreneur Hugh Hefner. In late 1953, he licensed the calendar photograph for the first issue of his magazine, Playboy. The resulting sales helped create a multimillion-dollar enterprise and made Hefner into a legendary—if controversial—figure.

Another upheaval surfaced a short time after the initial calendar scandal when it was discovered that Marilyn had been withholding information about her estranged mother, Gladys Baker. Baker had been in and out of mental hospitals for much of her adult life, and Marilyn had never enjoyed a positive relationship with her. In fact, as a child she’d only lived in her care on one occasion, and that ended when Gladys was taken away after suffering a complete mental breakdown. Since then, Marilyn had only seen her for short periods of time, and as soon as fame beckoned, the actress claimed that Gladys Baker had passed away. However, enterprising reporters went searching for the truth and discovered that the woman was actually alive. The story broke and once again Zanuck despaired.

While Marilyn was sickened that her ill mother was now subject to rabid media scrutiny, she owned up to her lie about being an orphan and explained that she had never wanted the public to find out about Gladys, due to her illness. The honesty worked yet again, and the public sympathized and understood.

AFTER SEVERAL YEARS OF working in films that required little more than smiles and wiggles, Marilyn grew bored and anxious to take on more significant parts. Thankfully, her spirits were buoyed when she was asked to work in dramatic films, including Don’t Bother to Knock (1952) and Niagara (1953). Henry Hathaway, director of the latter, thought the

actress magnificent, bright, and easy to work with, but the public preferred their Marilyn funny.

The actress had become a major star in lightweight comedy roles and musicals, as well as sultry publicity photographs angled to emphasize the blonde-bombshell look. Recognizing that these films and photos were a winning formula for Marilyn, Zanuck was happy to cast the actress in cheesecake roles forevermore. What he and others didn’t count on, however, was that Marilyn was not. In fact, she was growing more frustrated with every script that came her way.

Jane Russell, Marilyn’s costar in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953), predicted in March 1953 that the actress would not remain quiet about her discontentment for long. Speaking to Erskine Johnson, she said, “[Marilyn’s] going through the same thing I went through. She doesn’t like what the studio is doing to her and she doesn’t know how to say no. One of these days she will learn as I did. She’ll start swinging axes.”

Unfortunately, in an era and industry filled with male dominance, this was easier said than done. The cheesecake image was stifling, as was the fact that Fox insisted on putting Marilyn into film after film with scarcely any break in between. This gave her no time to really engage with the character, and it was literally a case of taking off one costume and putting on another, while still trying to remember all the dialogue and cues. Eventually, the twenty-seven-year-old actress came to realize that she would have to do something to rectify this situation. And as Jane Russell predicted, she did indeed.

In late 1953, Fox announced that Marilyn’s next picture would be the frothy musical The Girl in Pink Tights. Described by the publicity department as “a spectacular musical romance of little old New York,” the film was to be set in 1900 and feature Marilyn as a small-town schoolteacher who wants to sing opera. She moves to the city, only to find that her dreams aren’t so easy to fulfill, and ends up working as a saloon singer and dancer. Along with Marilyn, the cast was to include Frank Sinatra, Dan Dailey, Mitzi Gaynor, and Van Johnson.

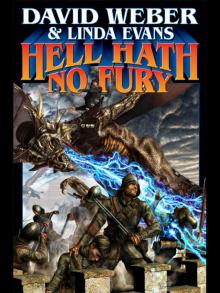

Hell Hath No Fury

Hell Hath No Fury The Mammoth Book of Hollywood Scandals

The Mammoth Book of Hollywood Scandals Marilyn Monroe

Marilyn Monroe The Girl

The Girl Racing the Moon

Racing the Moon