- Home

- Michelle Morgan

The Girl Page 6

The Girl Read online

Page 6

Marilyn looked particularly beautiful, dressed in a white ermine coat, satin cocktail dress, and heels. She was keen to show that the move to New York had little to do with dress style and everything to do with control. Announcing that she had just formed her own production company with Greene, Marilyn explained that the purpose was to expand her career into producing films, as well as television and other projects. When Marilyn added that she now believed herself to be a free agent, lawyer Frank Delaney nodded and confirmed that she no longer had a contract with Fox. As far as he was concerned, the agreement negotiated in 1951 had been abandoned by both parties, and The Seven Year Itch was filmed under a single-picture contract.

This answer seemed to buoy Marilyn’s confidence to no end, and when asked why she had walked out of the studio, the actress replied that her two most recent movies—River of No Return and There’s No Business Like Show Business—were not to her taste. She did not like herself in them, she explained, and in the future she wanted nothing more than to be able to choose her own roles. The actress then cited The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoyevsky (aka Dostoevsky) as an example of the kind of part she’d like to be considered for in the years ahead.

The press reaction to the conference was mixed. Hedda Hopper wondered if Marilyn had ambitions above her limits and told readers that she seemed to be carried along by her new advisors. She reported that some attendees at the press conference were heard to query what they were even doing there. “There has been a change in her public relations,” said another journalist, “and even the most charitable of her admirers can’t think this change is for the better.”

Reporter Jim Henaghan had a long friendship with Marilyn, but even he was worried. “Milton Greene has been a disturbing influence on Marilyn’s life,” he said. “He has brought about changes that might very well end her career.” He described the press conference as “one of the most bizarre in entertainment history.”

Even Marilyn’s friends and colleagues wondered if she had made the right decision by fleeing Hollywood. Natasha Lytess—who was fretting about the possible loss of her job—declared that nobody was indispensable and Marilyn may be forgotten if she didn’t return. Director Jean Negulesco said, “She is one of the most talented actresses I’ve ever worked with, but I don’t think the public would accept her in different roles. She’s stubborn.” He made clear his belief that she should have stayed working for Fox instead of branching out with Milton Greene.

The truth was, Marilyn wanted to show the world that a woman could be glamorous and blonde but still be an intelligent human being. In her mind, it did not have to be one or the other, but because this was such a revolutionary idea for a woman in her position, she was ridiculed for it. “I realized that just as I had once fought to get into the movies and become an actress, I would now have to fight to become myself and to be able to use my talents. If I didn’t fight I would become a piece of merchandise to be sold off the movie pushcart.”

Struggling to be treated as a serious human being was not a new experience. Marilyn had been laughed at in the past and just carried on striving toward her goal. It was all she could do. “I was born under the sign of Gemini,” she said in 1952. “That stands for intellect. I don’t care if people think I’m dumb. Just as long as I’m not!”

One person who did enjoy the press conference was reporter and high-society hostess Elsa Maxwell. While she was as perplexed as everyone else about the true nature of the event, it had given her the opportunity to meet Marilyn, which she had wanted to do for quite some time. Afterward, she wrote that an unnamed Fox employee had reprimanded her for being sympathetic toward the actress in her articles. “You don’t seem to get the idea that she’s on her way out,” he said. “A year off the screen and she’ll be washed up! We can find a dozen like her!” Maxwell laughed the incident off and insisted that if executives thought they could find another Marilyn, they were wrong.

After the press conference, the two women met again many times. Describing her as the most exciting girl in the world, Maxwell told Marilyn that it must have taken a great deal of courage to walk away from Hollywood. “No Elsa,” she replied. “It didn’t take any courage at all. To have stayed took more courage than I had…. All any of us have is what we carry with us; the satisfaction we get from what we’re doing and the way we’re doing it. I had no sense of satisfaction at all. And I was scared.”

Several days after the MMP press conference, Marilyn quietly flew back to Hollywood with Milton Greene to reshoot the skirt-blowing scene for The Seven Year Itch. When friends caught up with her in the studio commissary, she told them that she was still intent on running her own company and had no intention of speaking to studio lawyer Frank Ferguson or any other Fox executive. When she returned to the studio on January 13, it became clear that they wanted her there to do publicity photos and tests for a film called How to Be Very, Very Popular. Instead, Marilyn locked herself in her dressing room and refused all communication. The studio was incensed and demanded that she report to Lew Schreiber’s offices on January 15 to discuss the new film. Instead, Marilyn hopped onto the next available plane and was back in Manhattan before many realized she was gone.

Dented by the realization that Marilyn was still determined to live on the East Coast, Twentieth Century Fox announced that no matter what the actress might say, she was still signed with the corporation until August 1958. They added that everyone was incredibly happy with the dividends earned from her latest movies and there was no intention of ever putting her into The Brothers Karamazov. The spokesperson then took a pointed swipe toward her acting talents. As far as he was concerned, while Marilyn had tried her luck at other studios as a starlet, no one but Fox had chosen to sign her to a long-term deal. “That, brother, was criticism,” wrote columnist Thomas M. Pryor.

Still sure that Marilyn would run back when she came to her senses, Fox continued preproduction on How to Be Very, Very Popular. They then made the unprecedented decision to release full details of Marilyn’s salary, and said that her current financial grievances were of her own making. According to the studio, she had actually been offered a supplemental contract in 1954, which would have seen her earn no less than $100,000 per picture. Since she hadn’t signed it, however, her previous contract was still in force. Ironically, it was this same issue that convinced Marilyn and her representatives that she no longer had any ties to the studio, since the introduction of a new contract must surely mean that the old one had been dropped.

Zanuck was not convinced and a statement was prepared by the legal department. “The studio will use every legal means to see that she lives up to every provision of [the contract],” it said. It was then added that during her time at Fox, every effort had been made to give Marilyn the greatest worldwide publicity possible, and to surround her with the best artistic talents available. As far as the Fox top brass were concerned, nothing was wrong at their end, and all blame was to be placed at Marilyn’s door.

Back in New York, the undeterred actress waved their comments off. She still did not consider herself under contract, and would most certainly not appear in the next inferior picture they had planned for her. In the end, Fox had to admit defeat in this particular battle. On January 18, the studio announced that Marilyn was suspended, and that Sheree North would star in How to Be Very, Very Popular. The studio went all out in trying to frighten Marilyn with the thought that North could replace her not only in movies, but in the public’s heart too. To that end, they enrolled the help of Life magazine, which gave North a full-color cover and five pages depicting how she was being groomed for stardom.

Full-page ads also appeared in other magazines, telling fans to look out for the new face, and similar press continued to be printed during 1955. When How to Be Very, Very Popular was eventually released, the studio pulled out all the stops in their Marilyn/Sheree comparisons. A photo of North and her costar, Betty Grable (who had also acted with Marilyn), appeared in many ads for the film, accompan

ied by the following Marilyn-themed declaration: “Remember Gentlemen Prefer Blondes? Want another one like How to Marry a Millionaire? Wasn’t it great with There’s No Business Like Show Business?” An arrow then pointed to Sheree, with the words “Sheree North! All the fireworks you’ll need in July!”

The ads continued in the same fashion in 1956 when another North film—The Lieutenant Wore Skirts—was released. Alongside a photo of Marilyn standing over the subway grate, one such poster asked, “Remember the skirts that blew up all over America? Now there’s something new in skirts,” with an arrow pointing toward Sheree North, who just happened to be starring with Marilyn’s Seven Year Itch costar, Tom Ewell.

But in early 1955, Marilyn remained unworried. They had tried to threaten her with Sheree North in 1954 when she rejected The Girl in Pink Tights. On that occasion, columnist Dorothy Kilgallen even announced that North would soon be working on a biopic of Jean Harlow, knowing full well that Marilyn was an enormous fan of the 1930s star. Nothing came of the movie at that point, however, and shortly afterward Marilyn was actually offered the role herself. She did not like or accept the script, but it surely must have felt good to know that despite the veiled threats, no actress could ever replace her and the studio knew it.

At the end of January 1955, Zanuck sent a memo to Fox president Spyros Skouras to inform him that the studio had shown a rough cut of The Seven Year Itch at the Fox Theater in Oakland, California. There had been great excitement from the audience, and at the end of the show, 253 people said it was excellent and 153 described it as good. Only one person out of the more than 400 who watched thought it was terrible. Zanuck was extremely pleased by the results of the test screening.

Shortly afterward, an anonymous but disgruntled Fox stockholder complained about Marilyn to none other than columnist Hedda Hopper. He insisted that Marilyn brought nothing good to the organization and should be fired permanently. This statement infuriated the manager of the Oakland theater where the recent preview had taken place. He wrote to Hopper himself and said that while the stockholders might not want Marilyn, the exhibitors most certainly did. “I thought the audience would tear the house down,” he said about the preview.

CRITICS WONDERED ALOUD IF Marilyn’s rebellious streak was just for show. Modern Screen even printed an article entitled “Don’t Call Me a Dumb Blonde,” which argued that “there is a small shrewd group that insists that the curvaceous blonde is mixed up… is suffering from delusions of grandeur… will never make any man a happy wife… has been following poor advice and has more luck than talent.”

Not so, said an unnamed but charitable friend. “More than anything else, Marilyn craves recognition as an artist, as an actress—not as a lucky, fatuous personality. She would like to cremate the dumb blonde reputation she never deserved.”

Journalists were intrigued by the whole situation, especially when it was revealed that she had been reading classical literature and visiting theatrical actors backstage. Marilyn herself showed no patience with their curiosity. When asked if her attitude toward life had changed, she merely replied, “I don’t think so.” She was speaking the truth. For many years, Marilyn had harbored a great love of classical literature and took part in various acting classes and courses. When asked in 1951 what she was currently reading, the starlet revealed she was engrossed in a biography of German philosopher Albert Schweitzer and the entire works of French novelist Antoine de Saint-Exupéry.

Nineteen fifty-one had been a pivotal time for Marilyn, in terms of putting down roots in serious acting, books, and music. Notes made by early biographer Maurice Zolotow reveal that her favorite authors that year included Thomas Wolfe and Arthur Miller, while the role she most wanted to play was Gretchen in Faust. An interview that also appeared in 1951 disclosed that Marilyn loved to discuss author Walt Whitman and composers Mozart and Beethoven.

Actor Jack Paar witnessed Marilyn’s literary tastes during the making of the 1951 movie Love Nest. When asked about the experience in 1958, he had the following to say: “Please get this straight. Some published quotes attributed to me have given the impression that I disliked Marilyn while I was working with her in Love Nest. This is not true. She was a nice, big, little girl, one who was constantly carrying books of poetry with the title visible, so you could see what she was reading. It seemed to me she always wanted to be an intellectual, but she thought it was something you had to join. This naturally bored me, and I was also annoyed because she was always late.”

People might have seen Marilyn purely as a young, sexy starlet, but in 1951—at just twenty-five years old—the actress made every effort to further her education. “A girl can get along for quite a while just because her contours are in the right pattern,” she said. “It isn’t enough, though, for a long-term program, especially if you want to pick up a thing or two about emoting.” While making Let’s Make It Legal (1951), Marilyn spoke to journalist Michael Ruddy: “I’d like to be smart and chic and sorta—sorta assured like Miss [Claudette] Colbert. But I guess first I want to be an actress—a good actress.”

In 1953, reporter Logan Gourlay met up with Marilyn in her small apartment. There, he spotted books by Shakespeare, Somerset Maugham, and Ibsen. “I’m beginning to understand Shakespeare,” she said. “Michael Chekhov has helped me a lot. I don’t like Somerset Maugham. He’s too cynical, but I like Oscar Wilde.” During the interview, she told the journalist that she was learning lines from The Ballad of Reading Gaol by Wilde. When they met up again, she recited the last verse perfectly and told him not to be so surprised that she enjoyed poetry. To another reporter she declared, “I’ve just discovered Tolstoy. He’s wonderful. I’m blonde but neither dumb nor dizzy.”

Marilyn disclosed to reporter Aline Mosby that she read the classics because she felt comfort from learning that like her, the characters often felt alone inside. “I’m trying to find myself now,” she said, “to be a good actress and a good person. Sometimes I feel strong inside but I have to reach in and pull it up. You have to be strong inside of you. It isn’t easy. Nothing’s easy, as long as you go on living.” Marilyn surprised photographer Philippe Halsman when he took a glance at her bookshelves and spotted works by Russian authors and other highbrow volumes. He recognized straightaway that despite her public image, she was trying desperately to improve herself.

Someone else who saw Marilyn walking around with great works of literature was David Wayne, her male costar in How to Marry a Millionaire (1953). He later told columnist Earl Wilson that she carried books by Kafka. “I don’t know whether she knew what she was reading,” he said, “but she was making a hell of a try. She was out to get somewhere.”

Photographer Earl Leaf confirmed how smart she was in December 1954. Talking of her early days in Hollywood, he stressed, “Marilyn thought of herself as a serious-minded, sober-sided dramatic actress. True, producer Lester Cowan’s praise department tried to pin the ‘Mmmm Girl’ label on her for the benefit of those wolves who can’t whistle, but sex had not raised its pretty head very high in her own dreams of the future.”

For anyone who thought they were original by laughing at Marilyn’s ambitions during 1955, they were mistaken. Four years earlier, she had spoken about the mentality she had come up against from a young age. “I was afraid to talk about what I wanted,” she said, “because I’d been laughed at and scorned when I’d seemed ambitious. You can’t develop necessary self-confidence unless you express yourself, and even after I got to Hollywood, I was afraid that if I did, I’d be conspicuous.”

By 1955, she didn’t care about being conspicuous, but this was met with a hostile reaction in certain quarters. Stories began to leak to the press from generally unnamed men who saw Marilyn’s strength as a threat to their manhood. An old friend of agent Johnny Hyde contacted columnist Steve Cronin to complain about the newfound independence. “I once thought that this girl had a good head on her shoulders; the kind of steady head success would never turn. Now I’m not so sure. I can’t under

stand why Marilyn fought with her studio. What made her turn down a new contract at $100,000 a picture? A few years ago the girl was starving. That’s why she had to pose for those calendar pictures. Now, she’s ready to start her own company. What does she know about producing pictures? I can’t help feeling that she has been the victim of bad advice.”

Another anonymous individual was said to have worked as a crew member with her on many movies, including There’s No Business Like Show Business and most recently The Seven Year Itch. His opinion was not positive: “I’ve been on a lot of pictures with her, and I must say I was surprised when she ordered a closed set [on Itch]. Didn’t want any visitors, didn’t want any reporters. That was the tip-off, at least to me. She was getting a little big in the head. I’ve seen a lot of players in my time. Tell ’em they’re getting conceited, and they call you a liar. But gradually success has a way of swelling the head. It certainly has swelled Marilyn’s, or she wouldn’t have gone off half-cocked.”

The way some reporters spoke about Marilyn made it look as though she had been coerced into taking her career in another direction by her new colleagues: chiefly Milton Greene and his lawyer and agent. While she did value the advice of Greene and respected his position in her company, she never forgot that she was the majority shareholder. “I would listen to his advice about a film script,” she said, “but I wouldn’t necessarily take it. I make up my own mind about everything.”

Reporter Milton Schulman could see clearly who was in charge. To him, Greene admitted that he was not a trained businessman and was willing to ask for advice. “I have no doubt as to who is the real Svengali of this relationship,” wrote Schulman, “and it is not Greene. Undoubtedly the partnership has already achieved considerable success. But the big decisions come from Marilyn.”

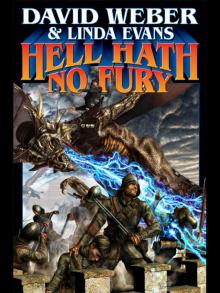

Hell Hath No Fury

Hell Hath No Fury The Mammoth Book of Hollywood Scandals

The Mammoth Book of Hollywood Scandals Marilyn Monroe

Marilyn Monroe The Girl

The Girl Racing the Moon

Racing the Moon