- Home

- Michelle Morgan

The Girl Page 18

The Girl Read online

Page 18

DURING LOCATION SHOOTING FOR Bus Stop, Marilyn had been invited to “a political whing-ding and hamburger fry,” hosted by the Speaker and Democratic members of the Arizona House of Representatives. Despite a plea from her press agent that her presence there would be good for business, Marilyn refused the invitation, and admitted that she had no interest in becoming embroiled in politics. She would soon come to regret saying that, however, when Arthur Miller dragged her into his own political affairs in the weeks and months ahead.

June 21 came and Miller made a much-publicized court appearance. It was the time of the McCarthy witch hunt, and the House Un-American Activities Committee had decided that Miller was worth investigating due to his attendance at a so-called communist meeting in the 1940s. During the appearance, the playwright asked for the return of his passport and the court demanded to know why he needed such a document. Miller replied that he would soon be going to London with the woman who was to become his wife. When questioned as to who that might be, the playwright confirmed it was Marilyn Monroe.

A huge mass of reporters was waiting for Miller outside the courtroom, and once again he announced that Marilyn was to become his wife. This set off a firestorm of attention, and within minutes she was besieged by reporters in the foyer of her Sutton Place apartment building. During the awkward, impromptu press conference that followed, Marilyn tried her best to answer the reporters’ questions, but it was difficult since the couple had merely spoken about an engagement in the past. They had not—as far as she was concerned—actually agreed on timing of a wedding. In fact, when discussing the subject of marriage, Miller had previously wondered if they should do it on his birthday, which was four months away. Out of everything that had happened in the past two years, the unexpected announcement of the Miller marriage was the first time Marilyn had felt utterly out of control. It was to be a feeling she would repeat in the weeks ahead.

When the House Un-American Activities Committee stated that the playwright would probably face contempt of Congress for not naming names, some of Marilyn’s friends and colleagues worried that she would be dragged into the fray. Of course, Fox president Spyros Skouras was first in the queue and begged Miller to cooperate. He refused, and Marilyn was exceptionally proud of his decision. When the studio asked her to step away from the drama for fear of blacklisting, she rebelled and stated that they had no right to tell her what to do. Marilyn fully intended to stand by her fiancé, and there was nothing anyone could say to stop her.

Fox executives weren’t the only ones worried. By now, the presence of Arthur Miller was presenting tension for the Strasbergs too. During a meeting between Marilyn, Miller, and themselves, the topic of blacklisting came up once again. After they tried to give some advice on the subject, Arthur made it clear that he did not appreciate their involvement in his affairs. Paula had good reason to be concerned, since blacklisting had happened to her during her early years in Hollywood. However, Arthur immediately became suspicious of the couple’s intentions.

Marilyn and Miller appeared outside Sutton Place on June 22, 1956, and had numerous photos taken by the reporters camped on the sidewalk. Marilyn assured everyone that it was “the happiest day of my life,” while Miller said he was determined to claim his passport. “I’m sure everything will work out all right,” he said, “but even if I don’t receive a passport we’ll be married as planned.” Shortly thereafter, they left Manhattan with Miller’s mother and headed to his home in Roxbury, Connecticut.

On June 29, 1956, Marilyn and Arthur applied for a marriage license and were then driven back to his Connecticut home by a cousin, Morton Miller. Behind them were a number of reporters, all desperately trying to catch an exclusive. Unfortunately for Paris Match correspondent Mara Scherbatoff and photographer Ira Slade, the car chase ended in unexpected tragedy. As the cars sped down narrow, winding lanes, Scherbatoff’s vehicle missed a corner and smashed straight into a tree. The journalist was thrown into the windshield.

The car was totally wrecked and debris was sprawled all over the road. Hearing the commotion, the Millers’ car ground to a halt and everyone—including Marilyn—went running back to see if they could help. Mara was laid on the grass and assistance was given to the other injured party. Miller was seen running through the woods for help, while a visibly shaken Marilyn was taken to the house. Reporters heard her shouting, “There’s been a terrible accident!” as she entered the home, and shortly afterward an ambulance was dispatched to the scene. Unfortunately, while Ira Slade could be treated for his injuries, nothing could be done to help Scherbatoff, and she passed away.

Almost directly after the accident, Marilyn and Arthur Miller held a scheduled press conference and were photographed with his parents. Everyone was on edge after recent events, and Marilyn and Milton Greene were seen furiously whispering to each other shortly before the questions began. When it was indicated that there should be some kind of statement regarding the accident, nobody was able to decide exactly how it should happen. “Somebody should question you,” Marilyn told Miller, and a journalist stepped in to tell the couple how they would normally work under the circumstances. “Who is going to question him?” demanded Marilyn, and when given the answer, she snapped, “Okay, fine!”

“Well, we just had a terrible accident on this road,” started Miller, “as a result of the mobs that have been coming by here. I knew this was going to happen; at least I suspected it was because these roads were made for horse carts and not for automobiles.” He continued by saying that the whole reason for requesting a press conference was so that the tragedy that had just played out could have been avoided. Marilyn looked terribly pale and nervous, but despite the horrendous events she had just witnessed, managed to keep herself together.

Perhaps realizing that Marilyn was not in a position to go into great depth during the interview, the reporters aimed most of the questions at Miller. Some were connected to his trial, while other journalists were more obsessed with finding out exactly when the marriage would take place. “You saw what happened today,” Miller replied. “If we make an announcement now, it might get worse.”

On hearing that there probably wouldn’t be a wedding anytime soon, the press returned to their New York offices. This gave the couple an opportunity to sneak off to White Plains to be married in a small, intimate ceremony. The only guests in attendance were Miller’s cousin and his wife, and Milton Greene. The bride wore a pink sweater and simple black skirt, while the groom dressed in a blue linen suit, white open shirt, and no tie.

Afterward, a spokesperson made the announcement of the marriage to the press, though he was met by a barrage of frustrated questions. “It’s as much a surprise to us as to anyone else,” he assured them. “They certainly pulled a neat one.” Not being able to get a statement from the couple, some journalists tracked down the police chief in White Plains to see what kind of security had been put in place during the ceremony. He assured them that “there was no question of controlling onlookers because it was all done so quickly.” When that wasn’t quite exciting enough, reporters contacted Miller’s mother, who had only a few words to add. “I guess they suddenly decided to go through with it without telling me,” she said.

At that point, the media seemed to give up on gaining any exclusives and went back to reporting the death of Mara Scherbatoff. The story ultimately made headlines around the world, and Miller was summoned to give evidence at the hearing. This was done in the form of a written testimony, and the couple was found to be completely innocent of any blame for the reporter’s death. Instead, it was decided that the driver of the car was solely responsible. Still, Marilyn believed that the death was a terrible omen, and never forgot the trauma of what she had seen.

Several days after the civil ceremony, another wedding was performed—this time Jewish in nature and with many friends and family in attendance. The bride—who had recently converted to Judaism—looked happy and beautiful in a tight gown with a small veil, while the usually

gloomy-looking groom appeared contented in his surroundings. Amy Greene later said that Marilyn had cold feet before the wedding and wondered if she should go through with it at all. However, any sign of those nerves was long forgotten by the time photographs were taken, and she seemed completely at ease on the arm of her new husband.

Joshua Logan and his wife, Nedda, put a lot of thought into a wedding present that would be totally unique. It consisted of Marilyn’s favorite Cecil Beaton picture in a three-paneled silver Cartier frame, with the signed print in the middle and a handwritten description of Marilyn by Beaton himself on either side. Marilyn absolutely adored the gift and kept it with her for the rest of her life, often showing it off to friends who visited her Manhattan apartment.

On May 1, 1969, nearly seven years after her death, the Museum of the City of New York put on an exhibition of Beaton’s work. In March of the same year, Nedda Logan wrote to Lee Strasberg—by that time caretaker of the Monroe estate—to ask if the gift could be used in the exhibition. Lee Strasberg wrote back nearly a week later to explain that Marilyn’s estate had still not been settled and the work remained in a warehouse. It was eventually released some thirty years later, and sold at Christie’s auction house for $145,500.

While the Logans were clearly ecstatic to see Marilyn and Arthur married, not everyone was overjoyed. Amy and Milton Greene were skeptical about whether it was the right decision for their friend and remained uncertain about their feelings for Arthur Miller. This was made even more apparent when the playwright voiced concern that Marilyn’s career was being mismanaged. While making Bus Stop, letters had gone back and forth between the couple, which discussed several arguments the actress had had with her business partner. Miller—perhaps unconsciously at first—wanted to help with that side of Marilyn’s life, and as a result, cracks started to appear in the working relationship between her and Milton Greene.

Because of what Miller regarded as interference in his affairs, he did not care much for Lee and Paula Strasberg either. Susan Strasberg believed that they actually had much in common, but their problems were based on a power struggle over Marilyn’s affections. However, Paula seemed quite tolerant, at least in the beginning. While speaking to reporter Vernon Scott, the drama coach described how Marilyn became “awakened intellectually when she married Arthur,” before going on to say that Marilyn’s initial move to New York had completely changed her life. “Instead of the Hollywood crowd and press agents, she is in the company of writers, critics, and creative people,” she said.

CHAPTER NINE

The Power Struggle

MARILYN AND ARTHUR MILLER arrived in London on July 14, 1956. They were met by hundreds of photographers, reporters, and fans at the plane itself, and by Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh inside the gate. The next day a press conference was held at the Savoy Hotel, where Marilyn was asked about the kinds of roles she would like to play in the future. “I would like to do Pygmalion,” she said. “As far as Shakespeare is concerned, I would like very much the part of Lady Macbeth, but at present that is just a dream.”

After a few days of press conferences, it was time to start work. Unfortunately, even at this early stage, it was clear that the making of The Sleeping Prince was not going to be smooth sailing. First of all, Marilyn disliked rehearsals intensely, whereas Olivier seemed to relish them. Then while introducing her to the rest of the cast and crew, the actor appeared to talk about Marilyn as though she knew nothing about acting at all—or certainly not the way they all knew it to be done. This was not a positive first impression, and the actress became guarded from the outset.

Circumstances were made no better when Olivier’s way of directing came across as patronizing and abrupt. After the sympathetic and calming way Joshua Logan had worked with her on Bus Stop, this was a shock to Marilyn, especially since The Sleeping Prince had actually been bought for her own film company. Marilyn’s reaction was to rebel against his orders, and she was often late on set. In return, Olivier decided she was awkward and unprofessional, and the relationship got off to a dismal start.

Another—much less surprising—area of discord was the fact that Laurence Olivier had absolutely no interest in the Method. In fact, it would be fair to say that a dislike of the practice was widespread among many British actors during the mid-1950s. “To espouse the Method in London,” wrote theater director and playwright Charles Marowitz, “is to preach paganism in the heart of Vatican City. People will not stand for it.” He concluded that the Method was “the mid-twentieth century’s favorite running gag, and as long as its emblem is a torn T-shirt and an actor picking the fuzz out of his navel, it will remain that way.” The problem was made worse when opportunistic, London-based “teachers” of the Method began advertising their services purely because they had read Stanislavski’s books An Actor Prepares and Building a Character. This was controversial since they had never actually practiced the technique in their lives but thought themselves qualified to take students’ money purely through reading about it.

Olivier was never going to support or appreciate Marilyn’s acting technique, but one person who did was Dame Sybil Thorndike, who had been hired to play the eccentric mother-in-law. She was a magnificent and highly successful actress who turned seventy-four years old during the making of The Sleeping Prince. Despite being rather a dominating figure, she showed great patience with Marilyn and supported her on many occasions. “She is quite enchanting,” Thorndike said in September 1956. “There is something absolutely delightful about her. She is not at all actressy.”

Marilyn adored Thorndike, and even though she rarely spoke to anyone on set, she found it easy to engage with the matriarchal figure. One day the thirty-year-old actress asked her older colleague just how she had so much energy. Thorndike said it came through being happy, in love, and working, while at the same time making sure she was never separated from her husband.

Once when Olivier was complaining about what he classed as Marilyn’s poor behavior, Thorndike interrupted, telling the actor that Marilyn was the only member of the cast who knew how to act in front of a camera. Marilyn found out about the intervention and was immensely grateful; she couldn’t quite believe that someone as respected as Thorndike had spoken up for her in such a manner. Actually, Thorndike was no stranger to the differences in acting techniques, and had actually talked about it two years before she began work on The Sleeping Prince:

Apart from closing theatres and causing an overcrowding of the acting profession, the advance of mechanized entertainment has considerably changed the style of acting. The influence of the screen has tended to make it more naturalistic. The heroic flourish associated with Irving, Tree, and Bernhardt finds no place in the theatre of today. It belongs to another age. On the other hand, there is a higher degree of sincerity. Neither actors nor audience are content with stage tricks. They both prefer them to be hidden and the resulting realism gives the impression that actors live their parts.

Out of everyone on the set of The Sleeping Prince, it was the eldest woman who seemed to understand Marilyn the best. While this astonished the actress herself, it really shouldn’t have. Dame Sybil Thorndike was always extremely interested in young people, and her grandchildren educated her on the kinds of plays currently in fashion. Within her work, she was always first to help any actor who needed guidance. Actor Henry Kendall later recalled that everything he knew about acting had come from working with Dame Sybil in the theater. As a result of her open mind and modern ways, Thorndike was much more qualified handling Marilyn than Laurence Olivier could ever hope to be.

In fairness to him, Olivier was not the only person who did not appreciate Marilyn as a fully formed actress. Just days after her arrival in London, Mr. G. R. H. Nugent, joint parliamentary secretary to the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, and Food, gave a talk to delegates at the National Whaling Commission in London. He announced in the most sexist way imaginable that Marilyn Monroe had arrived: “She has obviously come to England to dispu

te the saying of our great literary man, Dr. Johnson. He adjured us never to believe in round figures. One has only to take one look at her to see the truth that round figures do exist. Even without the assistance of a by-product of your industry, which has helped ladies’ figures.” The delegates cheered and laughed at the remarks, which were even translated for those who did not speak English.

At least one of The Sleeping Prince cast members was happy to make fun of the star. Intrigued by the way Marilyn walked, actor Richard Wattis decided to do an impression of her at Pinewood Studios. “I tried to walk like her down the corridor one day,” he told a reporter from the Aberdeen Evening Express, “but the only attention I attracted was from two policemen—who were not impressed.”

In a strange country and surrounded by people who seemed to be largely unfriendly, Marilyn decided to spend all her off time in the company of Arthur, Paula, and Milton. She then insisted on eating her lunch in the dressing room, which caused further friction between herself and Olivier. Staff at the Pinewood Studios restaurant stepped in to promise a menu of anything she wanted, but Marilyn still refused and instead a stove was installed in her suite of rooms and a private chef called in.

When publicist Alan Arnold asked studio staff what they thought of Marilyn, he was told she was “a bit stuck-up, but nevertheless sweet and charming.” He also claimed—or exaggerated—that no matter how hard they tried, nobody could remember a single word she had said, and this aloofness caused a great deal of tension. Actress Vera Day remembered overhearing some of the studio girls being catty about Marilyn’s appearance and claiming that they too could look like her if they wanted. “I’m telling you, they couldn’t,” said Day. “They could not.” Even Marilyn’s British bodyguard publicly announced that he thought Mr. and Mrs. Miller were boring, and that when they asked if he would go back to the States with them, he immediately said no. “It was dull working for them,” he said.

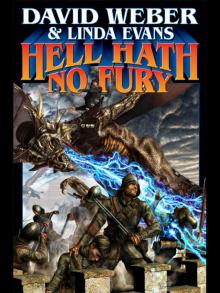

Hell Hath No Fury

Hell Hath No Fury The Mammoth Book of Hollywood Scandals

The Mammoth Book of Hollywood Scandals Marilyn Monroe

Marilyn Monroe The Girl

The Girl Racing the Moon

Racing the Moon