- Home

- Michelle Morgan

Racing the Moon Page 12

Racing the Moon Read online

Page 12

As the train pulled out of Wollongong station, I could see the lighthouse on the headland and fishing boats in the harbour. I kept looking for ships out at sea, and by the time we got to the high bridge over Stanwell Creek, I’d counted three.

‘You ever been in a ship, Pete?’

‘Nuh. How ’bout you?’

‘No, but a friend of mine has. Mac sailed to Batavia in the Dutch East Indies, and then flew to Amsterdam. They mustn’t be part of the British Empire because neither of them were coloured pink on Sister Ambrose’s new map.’ As the train entered a long dark tunnel, I closed the window before the smoke and fumes could come in.

‘Was ya dad in the war?’ Pete asked.

‘On the Western Front with Uncle George, but they never talk about it.’

‘Me real dad could’ve been in the same battalion as ya dad an’ uncle. He got killed in the war before I was born. I wanna go to war an’ fight one day, just like Dad did.’

‘Who would you fight?’ I asked.

‘The enemy.’

Fair enough, I thought.

‘Would ya come with me, Joe?’

‘Going to war isn’t like Racing the Moon, Pete. It’s not something you do on a whim. I think you’re jumping the gun, getting a bit ahead of yourself, mate. There’s not even a war for us to fight in. We could start off small, you know, selling eggs and newspapers, a bit of gambling and bookmaking on the side, that kind of thing. You ever build a billycart?’

‘That’s kids’ stuff !’

Looking out the window at the grimy factories and rundown shops along the railway line, I wasn’t keen to be going back to the city. But when I thought about seeing my family again, I started to get excited. As the train pulled into Central Station, Pete and I grabbed our cases and stood in the doorway, waiting for the train to slow down just enough to jump off, like I always do.

‘Joe!’

I could hear Kit but couldn’t see him. Then I saw a skinny arm waving and a blond head bobbing up and down in the middle of the crowd waiting on the platform. Mum and Noni were there too, dressed in their Sunday best. Dad was with them, looking thinner than he did six months ago.

‘Can you see your mum and little sisters anywhere?’ I asked Pete.

‘They’re always runnin’ late.’

‘I can wait with you if you like?’

‘I’ll be right. Ya family are all waitin’. I’ll see ya later, mate!’

‘You bet!’ Pete and I did our special handshake, finishing with a bear hug. As soon as I let go, Kit spear-tackled me, knocking me over.

‘Get up, both of you!’ Mum said, looking embarrassed. When I got to my feet, I lifted Mum up, swinging her around in the middle of the platform.

‘Put me down!’ she said, laughing.

Noni was looking the other way, ignoring me. She looked very grown-up, wearing a fancy hat and carrying a handbag just like Mum’s. ‘G’day Noni,’ I said. ‘You didn’t have to get all dressed up for me.’

‘I didn’t.’

‘She’s going to the pictures with Fred,’ Kit said.

‘Who’s this Fred character?’ I asked, winking at Kit.

‘A friend,’ Noni said, pulling on a pair of white gloves.

‘You’ve been behaving yourself for a change, I hear?’ Dad said, patting me on the back. It almost felt friendly.

‘Did you get my report?’

‘We sure did,’ Dad replied.

‘We’re proud of you, Joe,’ Mum said, wiping her eyes with a hanky. When I looked around for Pete, he was gone. Mum took hold of my hand: ‘Sister Agnes is very pleased with the progress you’ve made, so that means you can stay home and go to school here next year.’

‘Not to St Bart’s!’ I snapped.

‘You won’t be going back there, don’t worry about that,’ Dad said, clenching and unclenching his fists.

‘You’re not leaving me ever again, I won’t let you,’ Kit said, trying to put me in a headlock.

‘I’ll race you to the tram,’ I said, pushing him off me and getting a head start. Looking over my shoulder, I called out: ‘I bags the bed under the window!’ then started running for my life through Central Station to catch the tram back home to Glebe.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

I was inspired to write this book by stories my uncle told me about growing up in Sydney during the 1930s. Racing the Moon is set in 1931 and follows a year in the life of Joe Riley. I’ve tried to convey what it was like to be a boy, living and going to school during the Depression. I want the reader to be right there with Joe – seeing, feeling and experiencing everything that he does, to get a personal understanding of what it was like growing up at this difficult time in Australia’s history.

Very few families had a car or even a telephone back then. Most people in Sydney caught trams or trains to get around, or else walked. Aviators like Charles Kingsford Smith were flying around in small planes and commercial flights were just starting out. Ships were used to transport goods and people around the world, but only the wealthy could afford to travel. Computers weren’t invented, there was no television and the film industry was just starting up. Apart from listening to the wireless or gramophone records, people had to make their own entertainment at home.

Most people consider the American stock market crash in 1929 to be the start of the Great Depression. As prices for our primary produce (mainly wool and wheat) collapsed and overseas loan funds dried up, businesses closed, the government cut back on services and staff, and many people lost their jobs. The Bank of England advised our government on what needed to be done for Australia to be able to pay back its loans. In 1931, the government cut the basic wage by ten per cent, increased taxes and slashed spending. By 1932, around thirty per cent of Australian workers were unemployed, while many of those with jobs had to accept pay cuts or part-time employment.

The government provided some relief to the unemployed through the dole or sustenance (known as ‘susso’), but it was barely enough to survive on, and consisted mostly of food vouchers and coupons that could be exchanged for basic food items like bread, butter and meat. Soup kitchens and bread lines were organised by churches and other charities to help the destitute. There was no rent support provided by the government so a lot of people were forced to leave their homes and live in shanty towns or on the streets and in parks. Many people had to be creative to make ends meet during the Depression – just like Joe and his family.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

With many thanks to Lyn Tranter, Anna McFarlane and Rachael Donovan for their expert advice, ongoing support, enthusiasm for the book, and belief in me. Thanks also to Kate Goldsworthy and Nan McNab for their wonderful editing and proof-reading skills, and to Sue Hines and Irina Dunn who were enthusiastic about the book from the very beginning.

A big thank you and much love to my family and friends who read Racing the Moon during its adolescence and provided welcome feedback and encouragement: to Luke (my husband, soulmate and number one reader and supporter), Ben, Lindsey, Sylvia, Geoff, Wendy, Carol and Jonathan, and to Becky, Lee, Toby and Holly for their support as well.

With appreciation to David Wells and the Bradman Foundation for their authoritative information on Sir Donald Bradman and Eddie Gilbert.

With love and gratitude to Ron and Ray Morgan (my father and uncle), a couple of lads who grew up in the Depression.

And finally thank you to all my readers! To find out more about me, visit michellejmorgan.com.au. You can also find me on Facebook or Twitter @mjmorganwriter.

hare-buttons">share

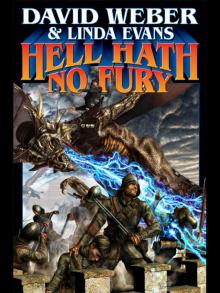

Hell Hath No Fury

Hell Hath No Fury The Mammoth Book of Hollywood Scandals

The Mammoth Book of Hollywood Scandals Marilyn Monroe

Marilyn Monroe The Girl

The Girl Racing the Moon

Racing the Moon