- Home

- Michelle Morgan

The Girl Page 10

The Girl Read online

Page 10

Marilyn ignored all threats and demands from Fox, and instead enjoyed throwing a surprise party for Milton Greene on his birthday in March 1955. She then did something rather unprecedented: she allowed photographer Ed Feingersh to follow her around New York City, going about her everyday business of shopping, riding the subway, and taking part in costume fittings. However, she was slightly concerned about her less-than-classy accommodation at the Gladstone Hotel, so by the time Feingersh arrived, Marilyn had moved into the more luxurious Ambassador.

The photographs taken during the shoot have gone on to become some of Marilyn’s most iconic, and have been used on postcards and posters throughout the world. One of the most famous is a black-and-white shot showing Marilyn leaning against the wall of her balcony, wearing a simple dress and holding a cigarette. The streets of Manhattan can be seen all around her, skyscrapers, modern and classic architecture, tiny cars and even tinier people. Everyone on the street was completely oblivious to the fact that the world’s most famous woman was gazing down on them, and yet there she was.

As a child, Marilyn used to gaze out of the orphanage window and see the RKO Studio water tower. Now she was gazing onto the streets of New York City as a famous movie star. What went through Marilyn’s mind during that simple but effective photo shoot? At times, she looks thoughtful, as though wondering what would become of her. At others, she is smiling broadly, her hands balancing her as she leans out over the wall, fully accomplished in mood and manner.

Other shots show Marilyn lying on her sofa, reading texts by Stanislavski and Motion Picture Daily newspaper. Her hair is untidy and her clothes casual, but she does not appear to care. The photos taken by Ed Feingersh that week show a person intent on success. New York had become a beacon—a strong, unmoving talisman to hold on to while she fought for her rights. Marilyn was a runaway, looking for bright lights and a positive future, and she could not return home to California without making her dreams come true first. Failure simply was not an option.

ON MARCH 30, 1955, Marilyn took part in a charity event at Madison Square Garden, which saw her sitting astride a pink elephant. As it clomped through the auditorium, fans way up in the farthest balcony cheered her name and waved furiously. Marilyn waved back and was so astounded by their support that she could not wait to tell Amy and Milton Greene all about it.

Journalists were happy to include photos of the actress riding the elephant, but some fans wondered if she had been scared. She assured them she was not. While bravery is something Marilyn is rarely given credit for, over the years quite a few photographs and stories have emerged showing her making friends with every kind of animal, from stray dogs and horses to big cats and bears. Her philosophy on her affinity for animals was simple: “Dogs never bite me,” she said. “Just humans.”

By early April 1955, Darryl F. Zanuck was in New York. He took the opportunity to hold a press interview to discuss the latest news from his studio, and, of course, the subject of Marilyn came up. After declaring that the company would do a major push toward finding new talent in the year ahead, he reiterated his belief that Marilyn was still under contract and their agreement was not expected to expire for another three years. Bizarrely, he then denied all knowledge of the actress’s plans to produce and star in her own company’s films, and stated firmly that if she did not fulfill her obligations with Fox, she might be liable for damages.

Meanwhile, Marilyn fielded other offers that came her way. One was from the Last Frontier hotel in Las Vegas to star in her own song-and-dance production. Marilyn balked at the idea and said she couldn’t possibly take part as she suffered from stage fright. However, Marilyn did say yes to an appearance with Milton and Amy Greene, on the April 8, 1955, edition of Edward R. Murrow’s Person to Person. During a meeting to discuss the television show, Murrow noted that Marilyn seemed interested but not overly enthusiastic about the interview. Then after talking for a few moments, she surprised the host by suddenly asking him about Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of India. The actress revealed that she had missed a recent show he had made about Nehru and was anxious to see it. Several days later, Marilyn arrived at Murrow’s office and they watched the program together. Afterward, she said that Nehru reminded her of Charlie Chaplin because of his expressive face. Murrow was so impressed with her interest in politics that he later sent her an album compilation of Winston Churchill’s speeches.

The live interview between Murrow and Marilyn, Milton, and Amy took place at the Greenes’ farmhouse. Baby Joshua was put down for his sleep and the three interviewees gathered in the kitchen. Crew members from the show hurried around, setting up cameras and microphones. A few minutes before they were due to go on, one of the crew mentioned that the threesome would be appearing before millions of people around the United States. This sent Marilyn and Milton into a nervous frenzy, but Amy remained calm.

Finally, it was time to switch on the cameras. The interview started with Milton in his studio, showing Murrow his vast collection of photographs. These ranged from a snap of his son to classic poses of Audrey Hepburn and, of course, Marilyn. Waiting in the kitchen, the star of the show was sitting with Amy, wearing a casual polo shirt and skirt. Considering she was a bundle of nerves before the event, Marilyn handled herself admirably, even when listening to inane questions about what kind of houseguest she was and whether she made her own bed.

The interview was somewhat awkward at times, such as in the middle of one question when Amy Greene suddenly interrupted Murrow and instructed the group to move to the den. Just as they sat down, the telephone started to ring. Several moments later, Milton got up to rummage around the sideboard for his pipe. The open fire crackled loudly in the background, and even the dogs made an appearance, but in all, the program was interesting, especially when Marilyn was finally asked about her new life.

Explaining that it was most important to have a good director, the actress disclosed that she had set up her film company hoping to make great pictures, and that she loved New York City and Connecticut and could often go around without anyone bothering her at all. This statement received a few chuckles from Milton and Amy, who then told a story about a taxi driver who started talking about Marilyn, not realizing for a second that she was actually sitting in the back of his cab.

The full appearance, including a studio introduction, took about fourteen minutes. While Marilyn might have been the star everyone wanted to see, it was Amy who stole the show. Looking as though nothing could ever faze her, she stepped in whenever Marilyn got stuck for an answer or seemed lost for words—so much so that afterward, some viewers decided she too should be in pictures. Amy herself remained insistent that her job was to look after Milton, Joshua, and, for the present, Marilyn.

By this time, Marilyn had left the Ambassador, but she did not move into her new apartment at the posh Waldorf Astoria Towers for several days. She saw the Greenes on the day after the Murrow interview, but then promptly disappeared. Concerned, they phoned Marilyn’s contacts in Hollywood to see if she had turned up there, but they had not heard from her in months. It was never brought to light where the actress had gone during her few days of absence, but wherever it was, it taught Milton a lesson. While everyone considered him something of a Svengali who kept other people away, Marilyn was more than capable of disappearing on him too.

After moving into the Waldorf, Marilyn embraced her new life. There, she entertained friends, practiced her exercises for acting class, and talked business with Milton Greene. On top of that were photo sessions where Marilyn posed in all manner of settings and situations. Milton’s natural way of shooting combined with her total trust in what he could do with a camera made the photographs some of the most beautiful ever taken, and they are still among the most prized by fans and collectors today.

In her spare time, Marilyn read consistently and listened to her favorite music: Ella Fitzgerald, Frank Sinatra, and many jazz musicians. “I’m insane about jazz,” she said. “Louis Armstrong and

Earl Bostick [sic]—it just gets stronger all the time.” This was not a new affection; Marilyn had loved Armstrong since her early starlet days, as well as Jelly Roll Morton, a jazz musician who had died in 1941. She also went through a phase of listening to music by composers Tomaso Albinoni and Ottorino Respighi, and she played a little piano, “The Old Spinning Wheel” and “The Long Way Home” her favorite tunes.

Away from friends and colleagues, Marilyn spent a great deal of time by herself, which she found calming and refreshing. On days like that, she would window-shop at Tiffany’s; sip coffee in small, quiet cafés; and buy creams and makeup at Elizabeth Arden. Many hours were spent closeted away in bookshops, reading and buying volumes on all manner of topics. Then she would admire art in the Metropolitan Museum, or go antiquing on Third Avenue. When asked how she managed to get around anonymously, Marilyn said she merely subdued her walk, wore no makeup, and put her hair under a scarf.

Anyone coming to Marilyn’s apartment hoping to find copies of Photoplay and Screenland magazines would be disappointed. When Pete Martin went to interview her, he noted a variety of interesting books on the coffee table, notably Fallen Angels by Noël Coward, Gertrude Lawrence as Mrs. A by Richard Aldrich, a condensed volume on Abraham Lincoln (she would later become friends with its author, Carl Sandburg), and Bernard Shaw and Mrs. Patrick Campbell: Their Correspondence by Bernard Shaw. Meanwhile, a recording of actor John Barrymore in Shakespeare’s Hamlet lay on the floor.

At night, Marilyn would lie in bed and listen to the sounds of the street below. The beeps from impatient cab drivers later became an observation exercise in her notebook. In the text, she pondered the idea that they were driving to support their families and go on vacation. She loved the sounds of the street outside, and the moon, park, and river were favorite sights. While appreciating natural beauty, she also wrote about nightmares in her notebooks, of strange men leaning too close to her in elevators, and a fear of being complimented, in case it was insincere.

Marilyn’s anxieties and lack of confidence were always a concern. Lee Strasberg encouraged her to do exercises out of strength, not fear, and taught technical ways to become stronger within herself. She remained frustrated that whenever she tried to express herself in a sincere way, there were always those who would dismiss her ideas and instead see her as a somewhat stupid person.

Still, Marilyn’s fears and inferiority complex never seemed to hold her back from trying to live her dreams and give thanks to those who had been kind to her in the past. She was forever humble, as demonstrated on April 26, when she unexpectedly attended the Banshees party for journalists at the Waldorf Astoria hotel. None of the waiting reporters knew she would be there, but everyone seemed ecstatic that she was. “Any success I’ve had I owe entirely to you gentlemen of the press,” she announced, before Earl Wilson snapped her with his camera and Gentlemen Prefer Blondes author Anita Loos desperately tried—and failed—to get close enough to speak.

HER ATTENDANCE AT THE Actors Studio eventually led Marilyn to become true friends with at least one of its students—actor Eli Wallach. She had seen him playing in The Teahouse of the August Moon and grilled him backstage about his work and whether he thought she could ever become a theater actress. Eli had explained what was required and Marilyn listened intently.

The actor always felt that theater offered a lot more artistic satisfaction than films or television, and had actually turned down numerous movie roles in order to return to the stage. During the course of his discussion with Marilyn, it was more than likely revealed that Eli had recently hopped over the Atlantic to play in London’s West End. Such freedom to move around was not something Marilyn had ever been used to in Hollywood, and it was something she would later experience as her own boss.

After seeing Eli perform in Teahouse, Marilyn got into the habit of seeing the play whenever she could. She would sneak into the balcony completely anonymously and spend hours soaking up the atmosphere. She also became close to Eli’s wife, Anne Jackson, and would sometimes babysit their son when they wanted a night out. One day after Marilyn told Eli that she adored Albert Einstein, she was somewhat surprised to discover a signed photograph of the man in her mailbox. After phoning numerous friends to share the great news, it was revealed that Eli Wallach had sent it himself as a joke. Marilyn appreciated his humor and hung the picture up anyway.

Showing competent business skills, Marilyn also helped Eli go over a contract, instructing him on which clauses to take out and which to strengthen. An article appeared in 1955 about this very experience, and although the comment was anonymous, it likely came from Eli. “Marilyn gave me the kind of advice I’d only expect to get from a Hollywood lawyer,” he said. “She knew the ins and outs and the fine-print tricks, better than an agent.” Another contributor added that Marilyn knew instinctively what was good for her in terms of business.

THE CLASSES AT THE Actors Studio emphasized expressivity, and Lee Strasberg felt that an actor needed to give an emotional performance, as well as deal with the feelings that this could bring to the surface. There were breathing exercises involved, and a great deal of repetition until the sentiment was absolutely perfect. Homework was necessary between classes, and an actor had to be prepared to work on his or her own. One of the most important talents practiced at the studio was the ability to cry in front of an audience. In this regard, students were encouraged to create anything in their mind to bring up the required emotion and tears.

“Marilyn had good experience of this because of her awful childhood,” remembers actor and student Joseph Lionetti. “She could be very vulnerable in a scene and cried easily, but she was beautiful. Lee said she could be a brilliant stage actress.” Indeed, at the time of Marilyn’s death, Lionetti remembers that the Strasbergs were actually hoping to create a play for the actress to perform in Manhattan. They believed that with her name and the sensitivity she was able to show onstage, it could have been a sellout for at least five years.

During the New York era, Marilyn was intensely interested in theater and attended dozens of performances. She was fascinated by the whole process of being onstage and interrogated many actors about the processes involved. Just some of the plays she attended included Shakespeare’s heavyweight drama Macbeth, A Hatful of Rain by Michael V. Gazzo, Middle of the Night by Paddy Chayefsky, and Inherit the Wind by Jerome Lawrence and Robert Edwin Lee. Arthur Miller’s A View from the Bridge became a favorite, and she was thrilled to support Susan Strasberg during her run in The Diary of Anne Frank.

Damn Yankees—a musical comedy about a man who sells his soul to the devil to become a great baseball player—appealed to Marilyn. Intrigued by the story, the actress called a meeting between her, Milton Greene, and writer George Abbott to see if there was a possibility she could become involved. Abbott loved her voice and decided she had a special quality, but the two did not work together on the play. “Marilyn should have a show written just for her,” he said. “With that personality, she’s entitled to it.”

Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? by George Axelrod starred Jayne Mansfield as a Marilyn Monroe–type character. Jayne had been described as a Marilyn wannabe and rival, so it was understandable that Monroe would be curious to see the play. However, when Edwin Schallert asked her about it a few months later, Marilyn denied ever having seen it, but she seemed to know an awful lot about it nevertheless. She was aware that the main character was being compared to her, but told Schallert that if she saw the play herself, she likely wouldn’t see any resemblance. The actress was steadfast in her opinion that the comparisons were probably only made because Mansfield’s character does not wear underwear, a comment Monroe had been rumored to have said.

At first, Marilyn was quite happy to be photographed whenever she attended the theater. However, this came to an abrupt halt when one of her Actors Studio friends chastised her for attending the opening of his latest play. According to the student, the press only chose to write about Marilyn and almost ignored the perfo

rmance completely. He claimed that the reporters’ fascination with her was what cost the play a long run. After that, she would often sneak into a play with her hair hidden under a scarf so as to avoid “spoiling” any more runs.

Being recognized could often cause problems for Marilyn. Random folk would sometimes shout at her from the balcony and even insult her clothes or hairstyle. Then fans would crowd around her at the intermission to have her sign their programs. At the end of the night, they often spilled out onto the sidewalk and followed her to nearby restaurants, where they would gawk at her over their menus. Reporter Logan Gourlay witnessed this one evening when he met Marilyn after a trip to the theater. As they reached a restaurant, Marilyn whispered, “Sit down in front of me and help block the view a bit. I don’t want to be stared at anymore tonight. I suppose I should be used to it by now. But I’m not.” Gourlay did as he was told, but two minutes later a waiter turned up to ask Marilyn for an autographed menu.

DURING ONE TRIP TO see a play called House of Flowers, Marilyn went backstage to talk to the composer, Harold Arlen. There, she was overheard telling the man that she was desperate to appear on Broadway and was considering appearing onstage before resuming film work. Just a few weeks before disclosing this, Marilyn had been approached by playwright Zoe Akins, who was working on The Trojan Party, a play she hoped the actress would take on as a stage production. The plans were never fulfilled, but had they been, it was sure to have been a great success. The play was intended as a follow-up to How to Marry a Millionaire, the movie Marilyn had starred in with Lauren Bacall and Betty Grable.

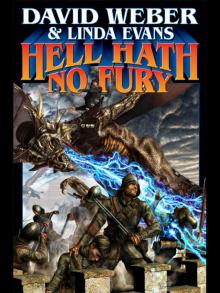

Hell Hath No Fury

Hell Hath No Fury The Mammoth Book of Hollywood Scandals

The Mammoth Book of Hollywood Scandals Marilyn Monroe

Marilyn Monroe The Girl

The Girl Racing the Moon

Racing the Moon